Indigenous communities of the Orinoquía: between violence and state abandonment

Three calls have been made to the institutions in order to find out what strategies and projects are being implemented for the ethnic populations of the region, who continue to wait for genuine interest that seems never to come.

Originally published May 13, 2023 in El Cuarto Mosquetero

LA PRIMAVERA, VICHADA—Indigenous communities from throughout Colombia’s Orinoquía region, organized under Tejido UNUMA, recently summoned representatives of the government to the settlement of El Trompillo in the municipality of La Primavera, Vichada, to demand a Rendering of Accounts regarding their petitions before the state.

"We inform the public opinion and national and international organizations that we are currently making a new call to the institutions of the Colombian state to sit down with the communities of the Tejido UNUMA to build strategies to solve the problems we face as inhabitants of the Orinoquía,” announced the organization on social networks.

The encounter, which took place from April 22 to 26, marked a new milestone for the organization of nine reservations, seven indigenous settlements and two campesino associations united in the fight to demand their rights.

The day before officials arrived, groups from the nine indigenous communities that managed to make the trip, given the difficulties of crossing such a vast territory with little or no roads, prepared for the meeting, organizing their documents and rehearsing their questions.

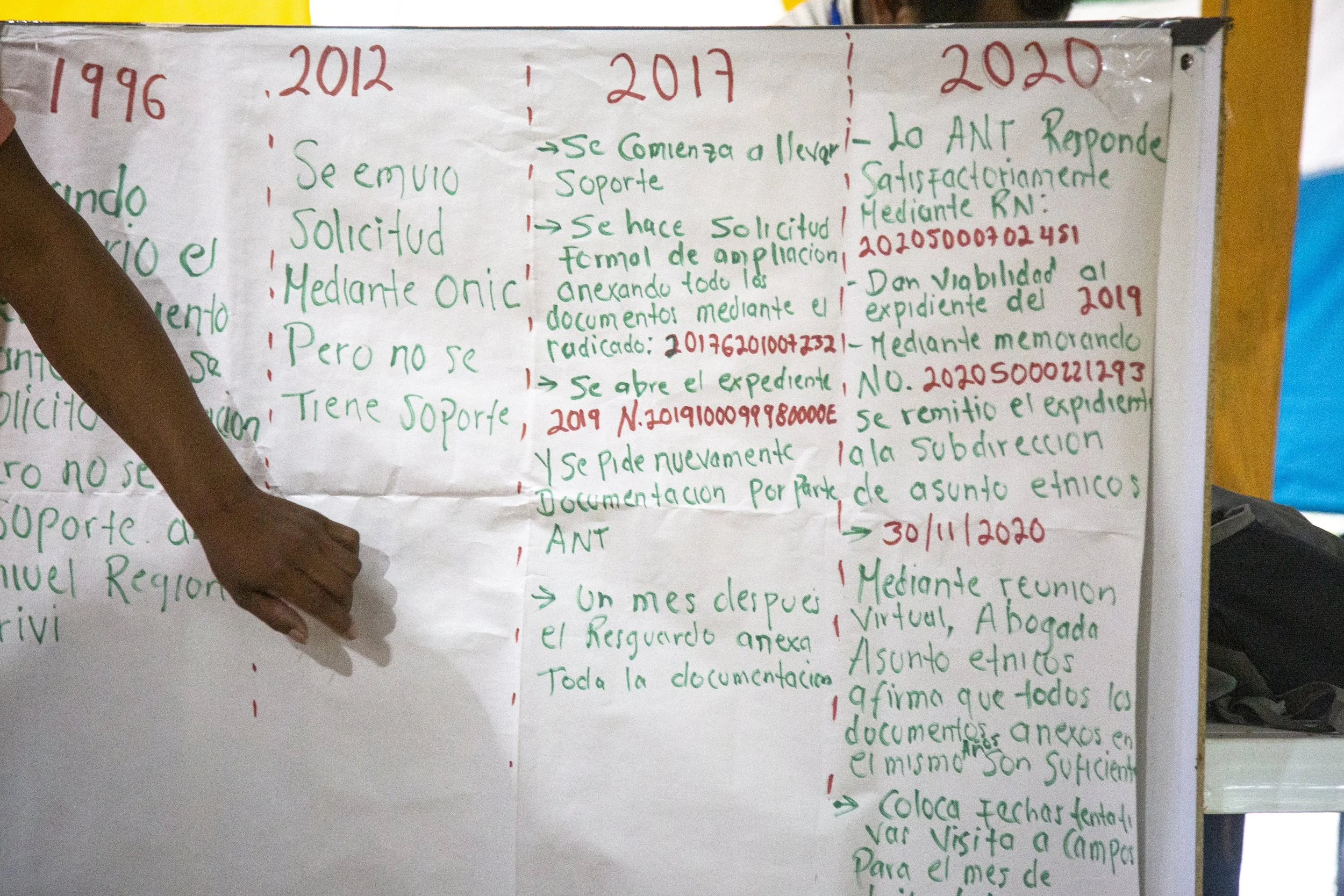

Using timelines, they mapped the administrative and legal processes that they have been navigating with the National Land Agency (ANT), Land Restitution Unit (URT), Unit for Comprehensive Care and Reparation for Victims (UARIV) and other entities to reclaim ancestral lands that are currently disputed by interests as diverse as landless farmers, agro-industrial and oil companies, illegal armed groups and even Mennonites.

María Hidaly Rodriguez, a leader and artisan from the Cocokü Kajönaë settlement in Puerto Gaitán, Meta, held up a finished timeline, but pointed out that “what’s written here is not even the first part of what we’ve suffered, what we’ve lived".

Behind the poster board, damp from the hard winter rain and scrawled with the sterile language of the state, are nearly eight years of struggle. There’s no room in list of petitions and court orders for the hungry days and fearful nights, nor of the hope that their children can live in peace in the land where their grandmother was born.

María arrived in the savannahs outside the village of El Porvenir, in Puerto Gaitán, in 2015, shortly after the state had recovered those lands from relatives and workers of Víctor Carranza, the powerful emerald tycoon who, according to the Truth Commission’s final report, was allied with Gonzalo Rodríguez Gacha, co-founder and head of the Medellín Cartel, and various landowners to fortify the paramilitaries that terrorized the Orinoquía.

When she settled near the site where her mother-in-law had lived part of her childhood–and buried her father–before being forcefully displaced, there was nothing but tall grass and the shadow of the Carranza clan. In the years since then, her community–and her children–have grown up with a constant threat that manifests itself in shots, burned huts and armed men who roam the savannas at night.

But it seems that their perseverance will soon be validated, as the last entry in Maria’s chronology is an important decision in favor of the community by the ANT. Only one procedure remains–an acknowledgment by the Ministry of the Interior–before the settlement of 53 families can be officially constituted as a reservation and receive a collective title to the land.

“We feel like, when you’re building a little house, and ooh! I'm finally finishing building it!” says María with a bright smile.

The perpetual conflict over land

But for others who made the trip to El Trompillo, the fight lies mostly ahead.

María Nancy Wemey Cove is a leader in the Yajotja community of the Waüipijiwi people. In 2017, along with the other members of his community, she was forced to leave the Caño Mochuelo reservation in Casanare, fleeing threats from illegal armed groups and from members of the reservation, including the forced recruitment of minors, cases of sexual violence against women, lack of access to health services and problems of governance and resources of the reservation.

“The decision of the Yajotja community to move and settle in a new territory is not due to a whim, but to a genuine interest in settling in a sacred place for the community and preserving their culture and cultural identity, and they do so in the exercise of their right to self-determination and autonomy,” affirmed the Constitutional Court in Judgment T-445 of 2022, in which it protects the rights to cultural identity, autonomy and self-determination, ancestral and collective territory, due administrative process and the ethnic subsistence of the Yajotja indigenous community of the Waüipijiwi people, located in the department of Vichada.

While they wait for the ANT to buy the ancestral lands for a new reservation, the 17 families live on just four hectares of rented land on the outskirts of the village of Agua Verde in La Primavera, a town that the leader is afraid to visit because of the hostility from their neighbors.

Since they don’t own the property, they’re not allowed to plant their own crops. So they have to eat what they can hunt or fish, and when there is no meat: mango stew.

But even foraging is not without its risks. Recently, said María Nancy, she was fishing in a public creek with her four-year-old daughter and her two grandchildren when a neighbor verbally accosted her. He told her: “You can’t set foot on this property, much less fish here."

Her young grandson, who hid behind her leg and clung to her pants, asked her: “Grandma, if he had shot you, what would have happened to us?”

Before the settlers arrived in the Orinoquía with a concept of private property, the savannas and forests were home to a diversity of indigenous cultures, many of them semi-nomadic who enjoyed the wealth of flora and fauna as hunters and gatherers. The native peoples had a deep relationship with the land but they didn’t formalize it with titles–a fact that the settlers exploited to take possession of it.

Throughout this process, the indigenous population has been the victim of systematic violence, from the “Guahibiadas” of the last century–in which colonists organized hunts of indigenous people with the complicity of the state–to the threats and accusations that define the relations between María and María Nancy and their neighbors.

Today they are forced to deal with the Colombian state to formalize their rights to the land that covers the bones of their ancestors, a challenge that has become increasingly complicated through the years of armed conflict and weak state presence in which conflicting claims and occupations–both legitimate and illegitimate–have accumulated.

The bureaucrats arrive

On the day of the Rendering of Accounts, the indigenous delegations and that of the Norman Pérez Bello Claretian Corporation (CCNPB), an organization that’s been working with communities in the Orinoquía for more than 20 years in defense of their human rights, began to arrive at the El Trompillo school before dawn.

According to representatives of the CCNPB, the Rendering of Accounts marks their third call to the institutions to present themselves in the territories, and was organized precisely because of the lack of participation on other occasions. Of the almost 65 governmental entities invited to participate in the fourth meeting of the Tejido UNUMA, held in March of 2023 in the La Llanura reservation in La Primavera, Vichada, only the ANT arrived.

While this third call was the most successful to date, the CCNPB remained disappointed in the official response.

Around 9:30 in the morning, the representative of the ANT connected to a video call projected in front of the school’s open-air meeting space. A delegation from the governor’s office of Vichada, including the governor himself, had already arrived, along with a representative of the UARIV, shortly followed by an official from the URT. After 4:00 in the afternoon, the mayor of La Primavera appeared with his delegation.

The delegation from the Ministry of the Interior never showed up, nor did any representative of the Public Ministry, which were among the 25 institutions invited, according to CCNPB documents.

Each of the institutions presented a report and took questions from the communities about their specific cases, which revealed the complexity of the bureaucracy and a pattern of petitions stalled as the agencies passed the buck.

For example, in the case of El Trompillo, the settlement where the meeting took place, the community has been waiting for more than seven years for a response to its request for its constitution as a reservation.

In his virtual presentation, the representative of the ANT, Leonardo Prieto, explained that the process was on hold until his office could verify the zoning status of the ancestral lands where the community had settled on the outskirts of the municipal seat of La Primavera

The official explained that if the properties are designated as “urban” or “urban expansion,” the ANT has no jurisdiction over the matter, which would then fall to the mayor’s office. However, under no circumstances does the mayor's office have the jurisdiction to grant the community a title.

Prieto asserted that his agency had requested that the mayor's office clarify the matter for the first time in December of last year, but after four months with no response, had filed a public records request the week before. For his part, Mayor Andrés Fernando Duque Cárdenas, assured that he knew nothing about the request, but promised to review the matter personally.

This direct dialogue between the offices, guided by the community and the CCNPB’s lawyers, was what marked the encounter as fruitful and unique within the history of the processes that the communities have been navigating, in some cases, for decades.

Another memorable moment in the morning was an exchange between lawyers from the ANT and the URT that revealed the daylight between their official positions.

In his update to the communities, Prieto from the ANT explained that the the La Llanura reservation’s request to expand their territory had been halted based on a line in a court ruling in favor of the community and that, according to Jaime Andrés Arias, legal professional of the URT, rather than suspend the community’s case, aims to freeze processes—such as purchases and sales of the land claimed by the reservation—that jeopardize the territorial rights of the community protected by the order.

“The National Land Agency makes the excuse that supposedly the court has suspended the process for the expansion or for the recognition of territory and that’s not true,” said the URT’s lawyer. “It is a misinterpretation… It would seem that it’s a pretext for not continuing with the processes.”

Arias promised to ask the judge to clarify this point, since the article on which the ANT bases its "misreading" appears in all land restitution orders and, therefore, has been used to justify delays in the cases of other communities and victims of armed conflict throughout the country.

While waiting for answers, the communities are exposed to serious violations of their human rights, since many are predicated on access to their own land.

For example, the Yajotja community, currently living on rented land, lacks clean water and basic sanitation since they can’t build aqueducts or sewage, they don’t have food security because they can’t plant crops, and since they can’t build their own school, the children of the settlement are forced to walk to the one in the village, where they’re forbidden from speaking their native language, according to María Nancy.

In response to what CCNPB lawyer Sebastián Vargas described as the Waüipijiwi’s "state of absolute vulnerability,” the governor of Vichada, Álvaro León Flórez, responded that as long as the community found themselves on borrowed lands, there was little his office could do.

For his part, Vargas pointed out that a sentence from the Constitutional Court issued last year to protect the Waüipijiwi’s fundamental rights explicitly orders the UARIV, the Government of Vichada and the Mayor's Office of La Primavera to arrange a working group dedicated to advancing projects to that end.

However, as of the day of the Rendering of Accounts, there had not been one meeting between the three entities, despite that fact the deadline stipulated by the ruling for the implementation of projects had come and gone.

Yet after months of inaction, representatives from the three offices, who now found themselves in the same room facing pressure from Vargas, set a date for the meeting on the spot.

At eleven o'clock at night, representatives of the government offices and communities present signed a document with 66 commitments reached throughout the day, 30 were to be honored by the mayor's office of La Primavera and the remaining 36 fell to the other five institutions. Among these agreements: the installation of the work table for the Yajotja community and the request for clarification of the Land Restitution Order.

While these may be small advances compared to the deep historical debts of the state towards the indigenous communities of the Orinoquía, the commitments demonstrate the development of the organizational capacity of Tejido UNUMA, since, with the support of the CCNPB, it managed to convene various governmental entities and promote a dialogue that generated concrete agreements.

The following day, members of Tejido UNUMA met to consider the next steps. For the immediate future, an Oversight Committee was appointed to ensure that the institutions kept their commitments. But with an eye to the future, those present drafted and signed an Act of Foundation as a social and political movement, an important step in expanding their presence at the national level, as in the model of the Regional Indigenous Council of Cauca (CRIC).

They agreed to organize an assembly in the coming weeks to draft the statutes.

Ombudsman issues Early Warning

For members of Tejido UNUMA, defending their territory continues to generate risks and threats from those who seek to strip them of it.

On May 10, the Ombudsman's Office issued an Early Warning for La Primavera, Vichada, due to the presence of several non-state armed groups that are fighting for territorial control among themselves.

“Indigenous communities and their traditional authorities, land defenders, human rights workers, community leaders and victims’ representatives risk the violation of their fundamental rights due to the presence and actions of illegal armed groups that dispute the control of the transnational border area with Venezuela and of the routes for the transit of illegal economies that cross the jurisdiction of this municipality,” explains the Ombudsman's statement.

Communities of Tejido UNUMA inside and outside of La Primavera, live with these threats.

A few days before the Rendering of Accounts, pamphlets showed up in the reservation of La Llanura signed by the Black Eagles, and in March masked men burned down a hut in the Cocokü Kajönaë settlement.

Last month, when María Nancy was traveling to La Llanura reservation for a meeting of Tejido UNUMA, two armed men showed up at her house asking for her. She still doesn’t know who they were or what they wanted.

The traditional leader knows that her family, especially her four daughters, worry about her, but she says she has to continue the fight she inherited from her father, a chief, to reclaim the land where her great-grandfather, Guerrero Yajotja, is buried.

"My daughter told me: 'Mom, don't go out because they’re going to kill you!' But I don’t care,” she insisted. “The important thing is to set foot on the land that we need,” a land that can’t be taken out from under them.

Additional reporting by Shirley Forero